Living With Cerebral Palsy, as an oldie.

The first thing I want to say about living with Cerebral

Palsy is that fundamentally, it is a pain in the backside. Now that I am a

permanent wheelchair user, one area that I have to be acutely aware of is pressure

points on my bottom. This may not be a highly sociable topic, but it is

absolutely crucial to a sense of well-being. I have a very good new pressure

cushion that, when you undo it, looks like many miniature teabags. But as you

move, the pressure points change. You would think that because these teabags

are quite hard, it would be extremely uncomfortable, but quite the opposite. It

is much better than my originally hard gel cushion.

I digress at this point because I am not talking about

Cerebral Palsy in old age. But being comfortable is absolutely essential to

well-being.

I was born weighing just 2lb at birth; I could literally

lay on the doctor's hand because I was so small. Doctors told my parents that I

was dead and that they should come over and say goodbye to me. My mother heard

a tiny squeak just like a mouse, and she called the doctors back, and they

realized I was barely breathing. All hell broke loose, and I was quickly put in

an oxygen tent and rushed to the premature baby unit. Where I stayed for some

three months until I weighed 5lbs and was able to go home. I did not have an

auspicious start to my life. In fact, when I was 18 months old, my mother was

told by a doctor, “take her home, forget about her, she’ll never be any good.

You’re wasting my time, your time, and everybody else's. This child is

spastic.” How I hate that term of calling someone a spastic; to me, it is as

derogatory as it can get. Though sadly, that was the way doctors referred to

people with disabilities in the '50s, and I was born in 1950.

Specialists told my parents that I would not live beyond my

teens, and it was always said in my presence. So I grew up thinking that I was

going to die anytime soon. As the years went on, I realised that I had not met

with their conviction. This kid was not going to leave this world too quickly.

Indeed, I am now 74 years of age, still working, still writing, and still

trying to change the attitudes that have been formulated in people's minds

regarding Cerebral Palsy. I still have a great deal of work to do. I will not

give up until I take my last breath. But I pray that won’t happen for a while

yet.

Mobility as a child was virtually non-existent. My body was

just like a rigid board due to Cerebral Palsy spasms. My legs were scissored,

one leg over the other, and my mother tells a story of trying to put a nappy on

me, which she said was like prizing my legs open as though they were a piece of

wood, and to get a nappy on me was almost impossible. Obviously, my mother

succeeded, and we were very grateful for cotton nappies because they could be

boiled and therefore eliminate some of the risk of infection.

My mother was a great one for massage; she consistently

massaged my neck, spine, arms, and legs. Gradually, I began to turn my head and

look towards objects.

My mother realised that I had no sight in my left eye due

to Retrolentalfibroplasia, which is a burning of the back of the eyes due to

oxygen damage. This was discovered by an Australian doctor who took 14

premature babies, bandaged the eyes of 7, and left the others uncovered within

the oxygen tanks. The uncovered babies became totally blind, whereas the first

7 had perfect sight—What a discovery. Now there is virtually no specialist

education for the blind or indeed specialist schools. I went to one in 1966,

and fortunately, due to having a good brain, I was able to learn braille, learn

to play the flute, and sing like a bird. Sadly, that is not the case today; I

am somewhat rusty with old age. But I still love to sing, even if it is just

for me.

My life changed when I went to the Bobath Centre, now known

as the National Bobath Cerebral Palsy Centre, with Nancy R. Finnie. She was a

wonderful Bobath therapist who started her life in a children’s hospital,

having learned about the “Bobath Approach”; she then took me with her to the

Bobath Centre where I became her training module. I was fortunate that I had

suddenly learned to speak at the age of 4, and mercifully, my speech was

perfect. No problems with Cerebral Palsy there! How grateful I am for that. I

have watched and listened to many people with Athetoid Cerebral Palsy who

struggle to formulate their words, have constant movement of their head and

hands, and obviously look as though they are severely affected with Cerebral

Palsy. Because I was able to articulate well, doctors at the Bobath Centre

wanted to hear what I had to say and see how I responded to certain tasks. I

was never able to draw; that was probably due to my sight loss. But I had

perfect articulation, and my mother always insisted that I spoke politely and

correctly to doctors and therapists. So I was an extremely good role model. The

“Bobath Approach” is one of total commitment. Parents had to agree to carry out

physiotherapy for two and a half hours a day—every day. Roberta Bobath, the

founder, was absolutely rigid on this point. If you were not prepared to make

the commitment, then the child with a disability would not be able to stay in

the system. Miss Finnie worked me incredibly hard, trying to implant normal

patterns of movement. For example, there was one simple task I had to cope

with, namely washing my face. This should be a simple task, taking a few

seconds, but for me, it was impossible. I would take my face to the face cloth

rather than bringing the cloth to my face. To begin with, I couldn’t see what

the problem was, so they showed me over and over again until my brain suddenly

got the idea, and I was able to perform this task successfully and the right

way round. What a victory!

Everything about Cerebral Palsy is small victories,

suddenly being able to move or roll onto your side and to crawl on hands and

knees, all done with the Bobath planting positions of good movement, again and

again. So that my brain got the message, and I was eventually able to crawl.

This was my means of mobility until the age of 11 when I had a hamstring

transplant on both legs, spending 6 months in plaster from thighs to toes. With

a plank of wood, rather like a broom handle, between my knees, keeping my legs

apart from one another. For this reason, I had to have my bed put next to my

parents, who would alternatively get out of bed and turn me over either from my

back or to my stomach. It was in the days of the old heavy plaster; the weight

of my legs was extremely heavy. I think this was where I first developed

problems with my sacrum and the pain that I have always experienced. After

surgery (one year later), I took my first steps with tripod sticks—just four

steps. But they were my giant leap for mankind. I could suddenly stand, and

more importantly, move on two sticks for the first time in my life—what a

victory. I can remember that my parents, brothers, and myself were standing

hugging each other with tears streaming down our faces. I had done it. Then two

years later, I had a detached retina out of the one eye I could see out of. I

became totally blind. I felt terrified to move, yet I had to go up and down the

stairs, and I was terrified that I would veer too much to the left and fall

down the flight of stairs. But somehow I managed it. Once I started at Dorton

House, School for the Blind, my life took off, and I was able to take flute

examinations with the Royal Academy of Music and I was to develop my singing

doing pieces from Handle Messiah.

When I left Dorton, I trained as a telephone switchboard

operator and worked for a bank in the City of London. The Commonwealth Trading

Bank of Australia was delighted to help me raise money for tailgates on

ambulances to help ferry people around with all kinds of disabilities. We took

people out every week to places of interest, restaurants, cinema, and other

activities. For the first time, they were not disabled people but people first

and people with disabilities second. They learned to have fun for the first

time in their lives, and they grasped every minute of it.

So what did this do for me in terms of going out and about,

meeting people, and projecting my work to improve the lives of people with

disabilities? Due to my blindness, I was always anxious about how I would cope,

especially finding my way to the toilet and managing at the food table. But

somehow I got through it. Naturally, there were people that were not

sympathetic when it came to helping me manage my food in a busy place. But I

coped with it because I wanted to get out there and socialise. You don’t realise

how hard it is until you are put in a position when you can’t do things or go

to places by yourself. It is a terribly frustrating time for a person with a

disability, and many of those feelings are still there today because society

doesn’t really cope well with people who are different.

In 1985, I met the man who was going to be part of my life

for the next 24 and a half years. We married in 1987. We were deeply in love

with one another, and he coped with all of my issues superbly until he became

profoundly disabled with Parkinson’s disease and subsequently Lewy-body

Dementia. Ralph died in 2011.

My life radically changed, and I then had to have 24/7

live-in carers, and the cost has been astronomical.

For those of us who are unable to propel themselves in a

wheelchair and have to wait for others to move us, that too is incredibly

frustrating. I now have a specialist wheelchair that is molded to my body to

help me sit up straighter. That is wonderful, and I am now in less pain due to

taking Gabapentin in liquid form (I cannot swallow pills) three times a day.

Although Gabapentin is a tremendous help, I am always conscious that it is an

addictive drug and would not wish to be on it from choice. Also, I now have to

be hoisted from bed to chair or chair to toilet. For that reason, I now have to

use incontinence protection because it would take far too long for me to get

hoisted and manage the toilet successfully. All of this is enormously

frustrating and costly. Government funding only meets about 1/3 of the costs of

incontinence such as pads, sheets, etc. Also, while much can be provided by the

GP in terms of creams, I prefer to use more natural healing products such as

Aloe jelly and Bee Propolis cream, but all of these are expensive and add to my

overall care costs as well as coping with my contribution to Adult Social Care

Services which now charge me £1337.78 per month. I have already bought my home

twice over in care costs. These are the hidden issues that most people have no

knowledge of. They will find that out in later life when they too may need

care. So my message is to keep as healthy as you can, as mobile as you can, and

keep an active mind for as long as you can. For all of these things will help to

keep you out of a residential care home. I am not decrying residential

care—some people have a great need for it. For those, there is no option. But

for those of us that are now in the later stages of our lives, we should be

looking at our homes, thinking about adaptations, and whether more thought can

be given to such things as wider doorways and ramped access. Those things may

keep you out of a care home for now at least. So good luck with all of it

because you are going to need it!

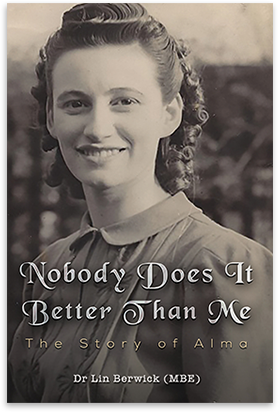

To read more about how Cerebral Palsy shaped my life and

how I coped with disabilities growing up, then read “Nobody Does It Better Than

Me. The Story of Alma. An inside to mine and my families life. Available on all

major book retailer websites.

Dr Lin Berwick MBE

Post Views : 193